- Home

- The town and the abbey

- The site from its origins

- The necropolis, city of the dead

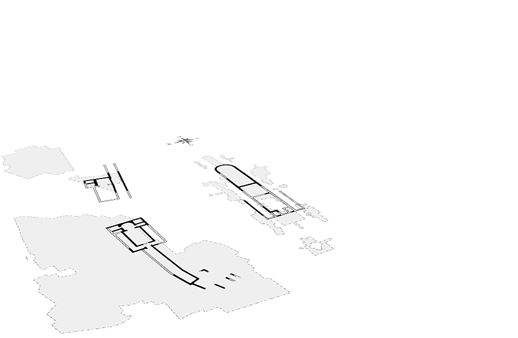

Reconstructed view of the monumental complex: seventh century © Ministère de la culture / M. Wyss ; A.-B. Pimpaud ; M.-O. Agnes.

Map of the monumental ensemble: seventh century CE

© Ministère de la culture / M. Wyss ; A.-B. Pimpaud ; M.-O. Agnes.

The basilica and its two necropolises

The Merovingian basilica was the result of at least two extensions to the original church. In its final state, the structure was nearly sixty metres long. It was in the first extension of this church that Michel Fleury discovered, in 1959, the grave of Queen Arnegunde. Hers was the best-preserved grave in the aristocratic necropolis, whose sarcophagi were mostly made out of stone and were found to contain sumptuous funerary objects.

To the north of the basilica, a vast necropolis spread out, with sarcophagi made of plaster. Excavations led by the Archaeological Service have uncovered more than two hundred graves, but we may assume that the burial zone originally contained nearly two thousand such graves. The inclusion of funerary objects in these graves of the exterior necropolis is evidence of a relatively privileged population.

The development of the monumental ensemble

At the edge of this cemetery there were at least three churches, which were later known as the Saint Bartholomew, Saint Peter and Saint Paul churches. The buildings were connected by galleries, which may have taken the form of open-sided covered porticos. Both the churches and the galleries were decorated with stucco and plaster painted yellow and red, as indicated by fragments discovered through excavation. Several capitals and small columns may also have been part of these structures.

This monumental ensemble had a funerary function, as indicated by the sarcophagi found in nearly every room and gallery. In terms of juridiction, this architectural framework that bounded the sacred zone of the cemetery offered the same right of asylum as the basilica; written sources from the period use the term atrium.

Origins of the monastery

All of these churches were served by a community of clerics. Under the reign of Dagobert I (629-639), these clerics were granted various privileges and exemptions that allowed them to organize the circulation of goods throughout their vast domain. The monks always considered Dagobert I to be their benefactor; when Saint Denis was chosen as the kingdom's patron saint, it was the king's own silversmith, Eloi, who was entrusted with the task of embellishing the saint's tomb. By choosing the basilica as Denis' final resting place, Dagobert granted Saint-Denis the status of royal necropolis. The Saint-Denis fair was created by Clovis II (639-657). Later, Clovis's wife Queen Bathilde removed Saint-Denis from the supervision of the Bishop of Paris, and established the legal statutes of the first monastic community. We may suppose that the monks took up residence in buildings located to the south of the basilica.

The beginnings of the town

It is extremely difficult to evaluate the size of the population that lived around the necropolis. Excavations have primarily revealed traces of craftspersons who worked with metal.

Not far from the basilica, archaeological investigations have uncovered three other, smaller necropolises. Two of them, at the time, were provided with churches-Saint-Martin-de-l'Estrée and Saint-Remi-but we are still not sure where the populations associated with these burial areas lived.