- Home

- Aspects of the daily life

- Ceramic production

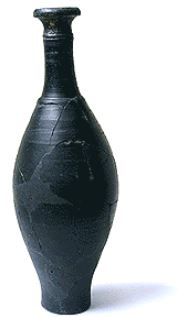

Ointment flask of Italic origin that has survived intact.

Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

Photo© J.-L. Godard / CVP.

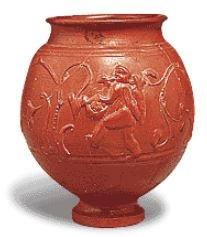

Arretine ware from central Gaul. 2nd century CE.

Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

Photo © J.-L. Godard / CVP.

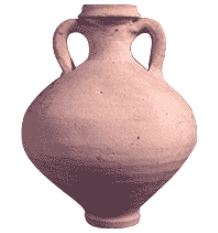

Amphora, produced by the workshop in the Rue des Lombards.

Commission du Vieux Paris.

Photo © M. Paturange / CVP.

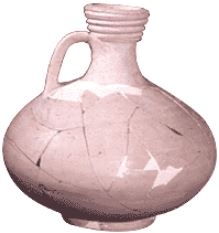

Jug produced by the workshop in the Rue des Lombards.

Commission du Vieux Paris.

Photo © M. Paturange / CVP.

History of ceramuc production

At the beginning of the Gallo-Roman period during the reign of Augustus, indigenous pottery was produced locally. It was the continuation of Gallic wares known as dark common ware. The first imports of ceramics from Italy began at this time; they included fineware, utilitarian pieces, Arretine ware and wine amphorae. Later, during the whole of the first century CE, the Gallic provinces supplied the Parisian market with fine ceramic tableware. By the mid-2nd century, local workshops had taken back the ceramic monopoly and the city was autonomous in the production of tableware.

Two types of production for two types of trade

Because of space requirements and their need for wood, workshops were relegated to the edges of the city. In this way, these early "industrial zones" did not disturb the city's inhabitants and they were near the biggest roads, which helped to bring them both raw materials and trade. Two types of workshops have been discovered: on the left bank, those located along the cardo supplied goods for the local market and the surrounding countryside. On the right bank, a workshop located near the Seine (in the Rue des Lombards) specialized in the production of amphorae-clearly focused on exports and the transportation of wine via the river.

Fineware flask. 2nd century.

photo ©A.-B. P / MCC MRT.

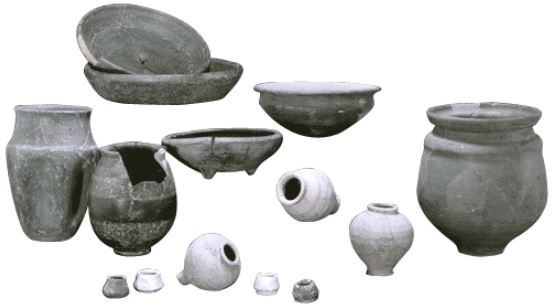

Pot, plate, three-legged bowl, wide-shouldered bowl, dish. 2nd and 3rd century.

photo © C. Rapa / CVP.

Fineware pot and drinking vessel. 2nd and 3rd century.

Photo © C. Rapa / CVP.

The simplest wares

Beginning in the 2nd century, the local market supplied the citizens of Lutetia with every imaginable kind of ceramic ware, from delicate goblets to large, deep platters used in the kitchen.

Common ware, recognizable by its gray colouring, was used for preparing food and for eating. There were cooking pots, pans for frying, shallow, three-legged bowls for cooking over a fire, and plates and deep bowls for oven use. Several of these forms came from the basic Gallic repertory.

Only a few jugs have been found. Some, because they were fire-resistant, could have been used to heat water; others, made from light-coloured clay, would have been used as tableware.

Fineware and tableware mainly consisted of various forms of goblets and several bottles.

Production of gray common ware ceramics in 2nd and 3rd century Lutetia.

Commission du Vieux Paris.

Photo: © C. Rapa / CVP.

Pottery kiln. Late 2nd-early 3rd century. Institut des Jeunes Sourds de Paris, 240, rue Saint-Jacques.

Commission du Vieux Paris.

Photo: © C. Rapa / CVP.

The pottery workshop in the Rue Saint-Jacques

The workshop in the Rue Saint-Jacques was discovered beneath the Institut National des Jeunes Sourds de Paris. Between the 2nd and 3rd centuries, this workshop produced common ware for the local market.

The kiln

The exceptionally well preserved kiln has a standard shape, and was found to have all of its parts, including the hearth, with an area for storing wood nearby, the stoke-pit, i.e. the main shaft with its opening, the kiln mouth, the firebox beneath the kiln floor perforated with small vents (flues) and the firing chamber, over two meters of which are still standing. The excavations revealed systems for modifying the fire's draw, thus regulating the temperature and conditions inside the firing chamber. The mouth could be closed with a flat tile, and some of the ducts blocked with pieces of pottery. A tile could have been placed over the chimney top, allowing the potter to move it if he or she wanted to bring in more air and release the smoke.

Additional structures

Several pits for holding clay were also discovered, as well as more temporary structures, perhaps basins for soaking, decanting or kneading the clay, or for wood storage. A large-mouthed well dug in soft, higher ground and surrounded by square coping was also discovered.