Weapons

The equipment used by hunters—and warriors—included a large bow made from yew (or, more rarely, ash) with symmetrical notches at each end to hold a bowstring made from tendons. Flint arrowheads were attached to straight shafts made from stump shoots of viburnum or hazelnut. The type of adhesive varied widely depending on the period and the individual: tar from birch trees or mixtures of resin and wax. Some adhesives, like bitumin, were even imported—unless it was the arrowhead and shaft that were traded. Other, somewhat more unusual weapons were also used in hunting: these include javelins tipped with a horn harpoon. Some of these were used with a throwing stick.

A variety of killing sticks were also employed, whose form and aerodynamics are close to those of the boomerang. These sophisticated and highly-polished throwing weapons were meant to hit the game with the sharp edge of splayed, knotty wood that was cut from a tree stump or root.

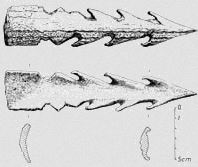

Harpoon made from deer antler.

Clairvaux, La Motte-aux-Magnins.

Ca. 26th century BCE.

Flint arrowheads.

Chalain, previous excavations.

Fragment of a yew bow.

Clairvaux, La Motte-aux-Magnins.

30th century BCE.

Killing stick.

Chalain 4.

31st century BCE.

Neolithic man's best friend

The dog is well represented at Chalain and Clairvaux in the form of still articulated skeletons. These could have been floating bodies of dogs. Their presence in villages and houses is attested by bitten and gnawed bones found in the waste areas and by sharp bone fragments found in hardened excrement.

There is no doubt that dogs were used in hunting. Even if they were small in size, the strength in a dog's jaw and teeth made it an efficient companion for tracking the game that the community needed—and in order to offer meat festivals that conferred status on the donor.

Dog skeleton.

Clairvaux, La Motte-aux-Magnins.

30th century BCE.